The fusion of history, archeology and genetics is cracking down on an 800-year-old Nordic mystery. Researchers from Norway used ancient DNA to prove a story from Sverris Saga, where a man’s body was thrown into a well. Genetic analysis reveals what man might have looked like and where his ancestors came from. The findings are described in a study published Oct. 25 in the journal Cell Press Science and the methods used can help scientists identify other historical figures.

“This is the first time that a person described in these historical texts has actually been found,” Michael D. Martin, a co-author of the study and a genomicist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, said in a statement. “There are many of these medieval and ancient remains across Europe, and they are increasingly being studied using genomic methods.”

[Related: Stone circles unearthed in Norway mark ancient children’s graves.]

of Sverris Saga

Old Norway Sverris Saga details the reign of King Sverre Sigurdsson and is an important source of knowledge about the region in the late 12th and early 13th centuries AD. One of the passages describes a raid on Sverresborg Castle outside Trondheim in central Norway that took place in 1197 CE. The writer mentions a dead man thrown into a well, but the reason why he was thrown into the well is much worse than just a run of the mill drowning. Historians suspect the corpse was dumped as a way to poison the main water source.

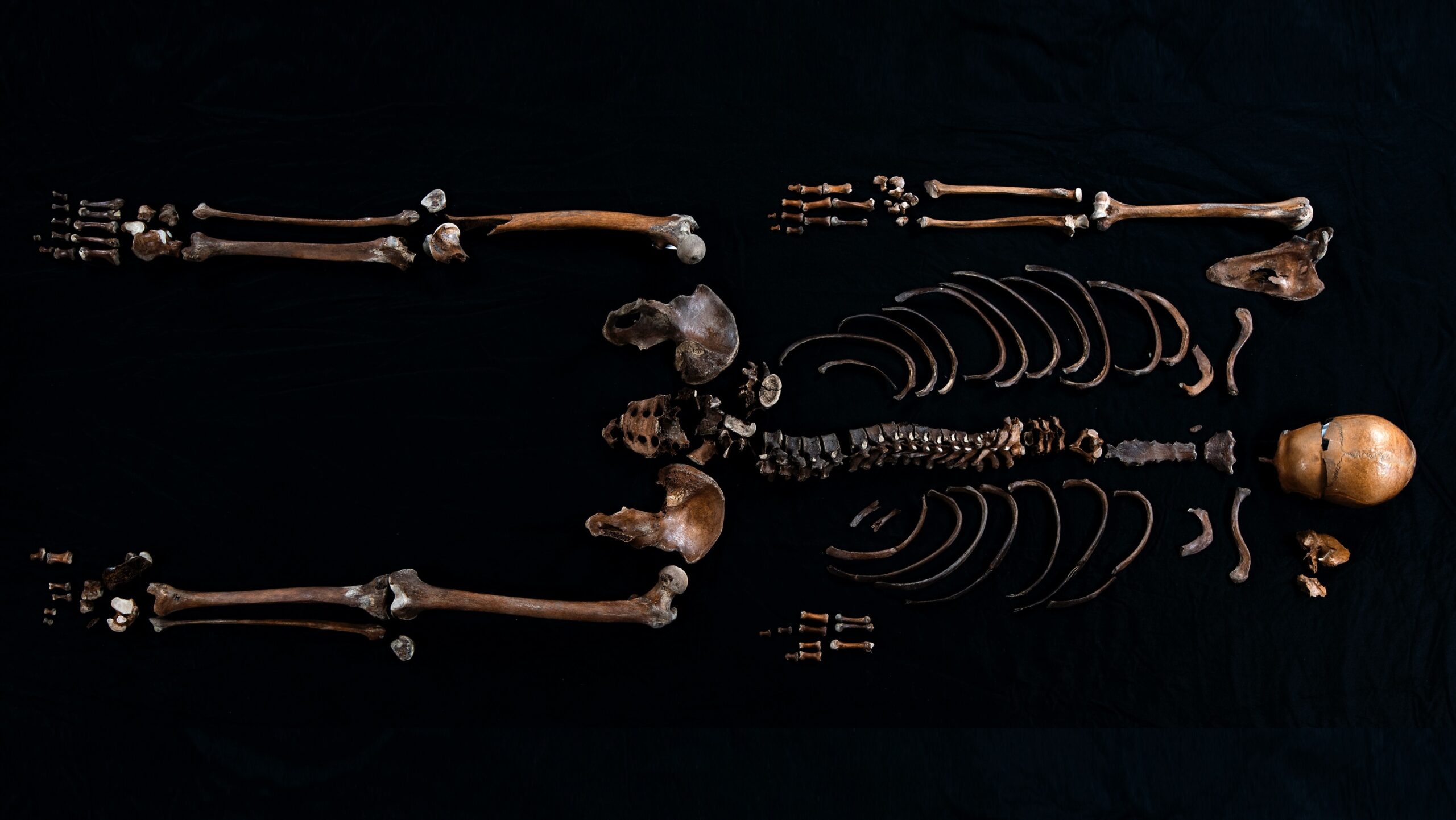

In 1938, bones believed to be those of “The Man” were found within the castle walls, but scientists at the time could not do much beyond visual analysis. Today’s scientists have radiocarbon dating and advanced gene sequencing technology that allowed them to build a stronger picture of Well-man’s identity.

Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the remains are approximately 900 years old. Research from 2014 and 2016 also confirmed that the body belonged to a male who was between 30 and 40 years old when he died.

“The text is not absolutely correct – what we have seen is that the reality is much more complex than the text,” study co-author and Norwegian Heritage Research Institute archaeologist Anna Petersén said in a statement.

“We can prove what actually happened in a more neutral way,” added study co-author Martin Rene Ellegaard of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

A 900-year-old genome

In this new study, the team used samples of a tooth from Well-man’s skeleton to sequence his genome. The team was then able to determine that he most likely had blue eyes and blonde or light brown hair. His ancestors were likely from the southernmost Norwegian county of today’s Vest-Agder.

To analyze this very old genome, they used a large reference dataset from the genomes of modern-day Norwegians and other Europeans through a collaboration with Agnar Helgason at deCODE Genetics in Iceland.

“Most of the work we do depends on reference data,” Ellegaard said. “So the more ancient genomes we sequence and the more modern individuals we sequence, the better the analysis will be in the future.”

[Related: Some modern-day Scandinavians lack the ancestral diversity of Vikings.]

According to the team, the discovery of Well-man’s bones and their connection to this passage in Sverris Saga gave them the opportunity to bring conclusions based on ancient DNA to historical study.

“While we cannot confirm that the remains recovered from the well within the ruins of Sverresborg Castle are those of the individual mentioned in Sverris Sagacircumstantial evidence is consistent with this conclusion,” the authors wrote in the study.

Tooth powder

Even with all this data and better research methods, there are still limitations to this technology. Sampling Well-man’s genome required removing the outer surface from his tooth, to keep it from being contaminated with any DNA by those who handled it during the excavation. The tooth also had to be ground into powder and the sample could not be used for further tests. The team was unable to obtain any clues about the pathogens that Well-man may have been carrying at the time of his death.

“It was a trade-off between removing the surface contamination of people who have touched the tooth and then removing some of the potential pathogens … there are a lot of ethical considerations,” Ellegaard said. “We have to consider what kind of tests we’re doing now because it will limit what we can do in the future.”

The team would also like to test samples from other historical figures, including Saint Olaf—Norway’s patron saint—who is believed to be buried near Trondheim Cathedral.

“So I think if his remains are eventually discovered, there could be some effort to physically describe him and trace his ancestry using genetic sequencing,” Martin said.